Hello People »

Art, Anger, & Acceptance

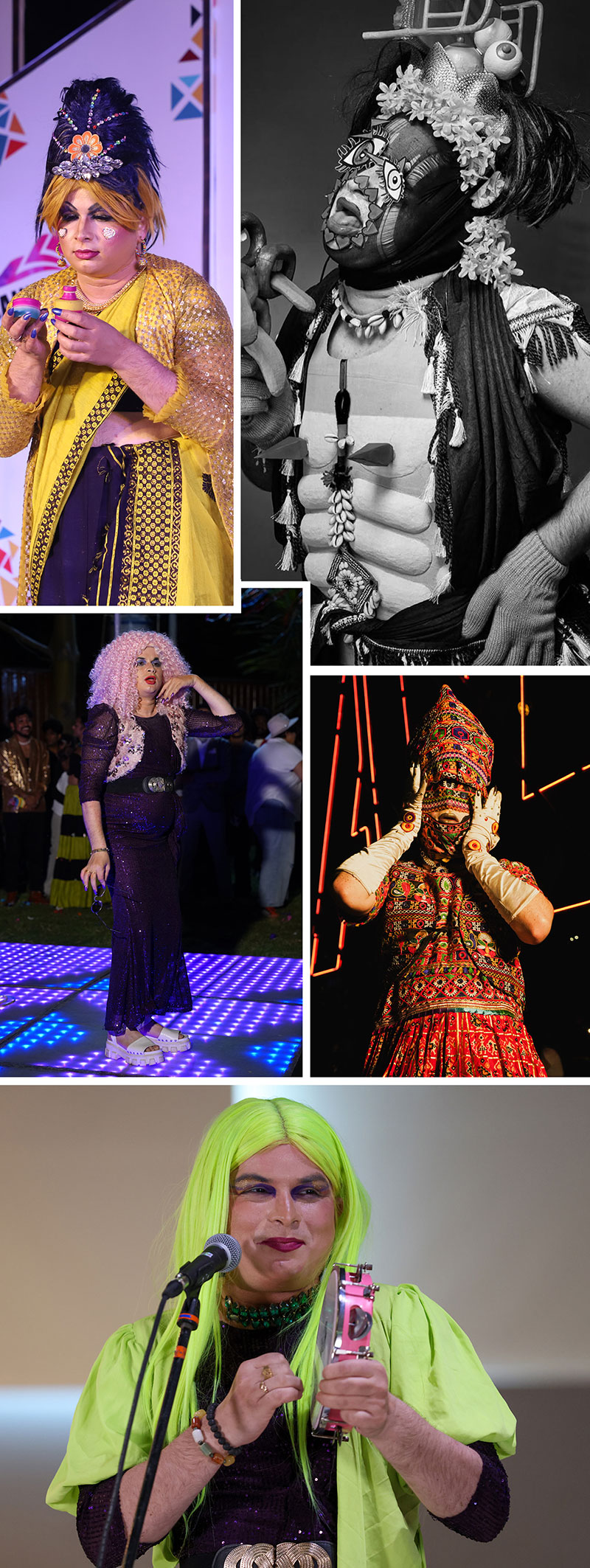

Drag artiste Patruni Sastry is breaking binaries with glitter, wit, and unapologetic theatrical brilliance

By Pranay J

Meet Patruni Sastry — the unstoppable force of sequins, sass, and storytelling! A drag queen, dancer, performance artiste, and proud parent, Patruni spins everyday life into glitter-drenched narratives that break binaries and celebrate queerness with unapologetic flair. From dazzling audiences in the award-winning documentary In Transit to strutting drag into living rooms via Bigg Boss Telugu, Patruni proves art can be bold, beautiful, and breathtakingly disruptive. With them (preferred pronoun), every performance is protest, play, and pure fabulous power.

Excerpts:

Let’s start at the very beginning — what was young Patruni like? Were there early signs of the expressive artiste you’d become?

I think my first inception of art or expression was while watching a Tamil film called Padayappa where Ramya Krishna was one of the heroines. I vaguely remember that in the film, the hero rejects the heroine and she screams out loud before breaking into a dance. That was the first time I was able to understand the connection between emotions and dance as an expression of that. She (Ramya) was dancing because she was angry. It connected. I thought I need to be angry, I need to scream out loud and dance. So, that’s what I have done since childhood and somewhere that became a very dominant trait for me — to use art as a way to express my anger, to start with. That also helped me in multiple ways. When I was in school, and later in college, or at any point I felt bullied, I would break into vigorous dancing. People would call me Thaliwale Bhaiya because I used to dance on a plate which is a proper Kuchipudi art form, by the way.

I would also sketch as a child. I was put in a boarding school and I would send letters and postcards to my mom with sketches of my crying face, with details like glasses and blood tears, urging her to take me back home. So, at that time too, I was very expressive in my art. I think that made it easier for me to pursue art full-time. I did learn Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam at a very young age and I started using those to navigate my own expressions.

You’ve carved out such a distinct space with your work — what moments or milestones in your life shaped that creative trajectory?

I think there were a couple of things which have definitely which have definitely influenced my path. One of them was connecting with queer communities in Hyderabad because they were my first audience. I was more of an inward community-based performer, but eventually moved to social/public performances. I think that was a significant difference because that made me realize my craft is meant not for the regular idea of it, but to kind of make it very agile and political in its own nature.

Another moment was when I started learning about drag. In 2017, I attended the Bangalore Pride, and I saw some drag artistes perform. And I felt the need to bring the same experience to my city. I started doing drag in 2019. It took me two years to decide and articulate what I wanted exactly. And since then, I have shifted from being an expressionist classical dancer to a drag artiste, which also defines my transformation with regards to my artistic work.

Over time, I started experimenting more with drag, creating educational pieces. A couple of my works which are really close to me are Sweekar, which is about giving birth to an intersex child; and Come Sit With Me, where I asked regular people in a park to come and sit next to me, knowing that I am a drag artiste.

The public performances which I have done for World Music

Day, or in collaboration with Telangana State’s AIDS Control Department are some of the other milestones.

Of course, I have received a lot of visibility after the web series In Transit, because I am the first alternative drag artiste to be visible on such a platform.

I am still creating a niche — how drag can be an educational space. My learning from the classical dance and my understanding of the current drag, the blend of both is what I believe makes my work unique, and also give it a flavour of being something which is more spiritual and traditional in its own nature.

What was your first experience with drag like? Was it a conscious artistic choice, an accident, or a calling that found you?

Drag wasn’t a conscious or serious choice. It started more as trial and error. I was a classical dancer, but I often felt a disconnect—my training didn’t always resonate with the communities I was performing for. That dissonance was strong, and during a visit to Bangalore Pride, I saw incredible drag artistes. Their work showed me the opulence, storytelling, and possibilities of drag. I was fascinated, but I didn’t imagine myself performing—I was still a “baby queer,” not out to my family or friends, and I didn’t know how to explain drag to people. But what I certainly wanted, was to bring drag to Hyderabad.

When I returned, a group of queer friends and I were discussing what Hyderabad lacked. Someone said parties, and another said drag artistes. That became the starting point. My initial idea was to train others in drag, not perform it myself. But when a friend challenged me—saying I couldn’t expect others to try drag if I wasn’t willing myself—that pushed me to step in. I initially imagined being a saree-clad drag queen.

On June 9, 2019, we held our first drag show. Many places refused because they saw drag as inherently “adult” or inappropriate, but finally, a small café opened its doors. We went ahead despite rumors that the event was “illegal” or unsafe. I expected around 21 people, but more than 500 showed up. That night, I realized the true power of drag—its ability to bring people together and create something transformative.

You’ve described your drag as more than performance — almost as protest. How do you define your drag in your own words today?

For me, drag is a four-letter word which says dress resembling a gender, and I say it in the simplest way that — for a musician, voice is their canvas, for an artist, a physical canvas is a canvas, and for a theatre person or a dancer, their body is a canvas. For a drag artiste, their gender is a canvas. We create an idea of a gender, a manifestation of a gender, and we exaggerate the idea of it and present it to the audience, sometimes questioning the binaries of gender and sometimes evolving and creating an imagery, which is a manifestation, for a lot of people, of their own gender visibility.

Drag, for me, is a very agile art form, blending with any kind of performative pedagogy. And drag, irrespective of age group, colour, caste, and gender, becomes a space for everybody to explore and create an exaggerated version of gender and present it to people.

In India, drag still exists in a mix of cultural reverence and misunderstanding. How have you navigated performing in that space?

The reason why people think drag is a western import is because I’m using an English word. Having said that, in India, drag has had multiple connotations. For example, we see how men dress up as women performing traditional art forms like Kuchipudi,

Bharatanatyam, and Kathakali. You would see the same in rituals like Theyyam and Bhuta Kola, where men would dress up as gods and then navigate the idea of prophecies. You would see titillating ideas of sensuality and sexuality when it comes to Tamasha or the Lavani art.

However, people still say that drag is not relevant, and it’s always a conversation I love having because there are instances where drag is seen as a borrowed art form from India. I feel that there’s no difference between a drag performer and a Lavani dancer or a Gotipua dancer.

However, for a ticket to a drag show, I get 18% of GST charged, whereas for a Bharatanatyam concert or any kind of Indian classical dance concert, the GST is much lower. So, you see the difference between how exactly a contemporary art form is treated just because we are using an English name.

How I navigate is I try to imbibe a lot of elements from these traditional art forms into my drag, like dressing up in sarees or singing folk songs while performing, and sometimes also blending my education with classical dance and music. I do this so that people can draw relevance to an already existing art form.

You’re also a parent, which is beautiful and rare to see represented. How has fatherhood reshaped you as an artist and human?

Fatherhood has opened me to a sense of circular life. Now when I come back home, I forget whatever is happening around and I just spend my time with my kid. It is very relaxing and soothing as a parent to just watch my kid. It also helps me to redefine my art so that it is accessible for my kid as well. When I started doing drag, it was very specific to a certain age group. And somewhere in the process, I too lost the idea of creating spaces where people can get involved irrespective of age. After becoming a parent, I understood what I can do to create performances and spaces where a queer parent can bring their child too. I was lucky to have my kid at the right time, because it was the time UK and US legislations passed a ban on drag, stating it’s unsafe for children. And here I was, a drag artiste, having my first child… Although it was a very conflicting situation for me, I realized that there is a purpose behind it, which is to tell people that being a parent myself and embracing an art which most parents think is not safe for the kids, I would be able to kind of bridge that gap and join the dots and say that drag can be accessible, drag can be child friendly as well.

I didn’t want to hide myself from being a parent versus being an artiste, because both of them are my babies — both my art as well as my biological kid. I take pride in having both and living my authentic life.

Is there a moment — big or small — from parenting that surprised you, challenged you, or simply changed your perspective forever?

The first time I performed drag in front of my kid, he was around one-and-a-half years old. I thought he would not recognize me in drag, but it was very surprising that he did recognize me! I was performing, and he stepped onto the stage and then people were just watching him, not me!

Every morning when I get up, I take my child in front of the mirror. We just watch each other in the mirror. And then suddenly he calls my drag name, Sas Who Uma. It’s a very sweet moment for me. My child plays with my wigs and accessories. That also gives me reassurance that he is able to see and accept me for who I am.

Where do you see your drag heading in the next few years? Is there a dream stage or collaboration on your vision board?

One of the biggest aspirations I have is to get a national award. Then, I definitely want to work in films — play a character with negative shades, or be a ghost in a horror film. I would love to collaborate as well as expand my presentation with schools and colleges and educational institutions. I also wish to open a drag school where we can teach and have a conversation about drag art and make it more accessible for people to learn about it.

What do you want to leave behind — not just as an artist, but as someone who broke molds and made space?

One of the things which I really want to leave behind is archival footages that people can see, refer to and then try to relearn about the art form. I don’t want to be inspirational but I want to be somebody who has lived their fullest life without any kind of fear. That’s the legacy I want to leave behind.

If you could whisper one sentence to every queer kid out there unsure of who they are, what would you say?

Queerness is a gift and one has to just believe in it. Also, anything is possible if you believe in it.